It's not enough to identify and diagnose a learning disability. Assessment processes are excellent in determining accommodations that might be needed to help an individual improve in an academic environment, as well as in skills development.

In this article, we'll delve deeper into some of the challenges that confront teachers, school districts, and other students when it comes to learning disability accommodations in a classroom environment, as well as special education needs. We'll offer a brief discussion on devising catered instructional plans for skills development, and offer a brief overview of how short-term and long-term educational development plans are created.

Utilizing Catered Instructional Plans for Skills Development

When it comes to teaching strategies for the learning disabled, a firm sense of direction and structure is vitally important. Strategy instruction is not a new approach to student-centered teaching, but it is one that is especially beneficial in helping students with learning disabilities or other types of disabilities learn, function, and remember what they have been taught.

Such strategies often focus on nontraditional methods of schooling and teaching, depending on the needs of individual children. For example, this may be achieved through different settings other than a classroom environment, teaching one-on-one, or through group-based activities.

Cognitive strategies are defined as those that are based on specific, action-based activities. This is especially beneficial for tactile and visual learners. Cognitive or metacognitive awareness strategies take advantage of a student's focus and attention when engaged in the learning process.

An example of metacognitive awareness is one that encourages the student to perform a critique on his or her assignment, tasks, or homework. While this is more directed toward older learners, the strategy aids in monitoring comprehension and encourages the student to understand, in greater focus, their own issues when it comes to reading, writing, and comprehending. Metacognitive awareness leads right into self-regulatory strategies, which encourage students to think of themselves in positive ways.

The strategic instruction model or SIM, is another popular method that has been used more than 25 years in the educational field. This strategy focuses on content enhancement, teaching methods, and routines that consistently help the teacher organize and deliver content in a learner-friendly and interesting way.

The focus of the SIM model is to encourage passive learners to become more active in applying their knowledge and skills in a variety of environments, including the basics of reading, writing, and math. It also helps them study and remember -- and motivates and encourages them to interact with others.

As you can see, creating instructional plans for skills development depends on many things: the student, the teacher, the parent, and the overall needs and goals of each when it comes to learning and skills development.

Not too long ago, any child diagnosed with a learning disability was automatically shuffled into a special-education class. However, Princeton University, in a research paper regarding the future of learning-disabled children, presented a thought-provoking comment in a book written nearly 26 years prior: "LD is not a distinct disability, but an invented category created for social purposes. Some argue that the majority of students identified as having learning disabilities are not intrinsically disabled, but have learning problems caused by poor teaching, lack of educational opportunity, or limited educational resources."[1]

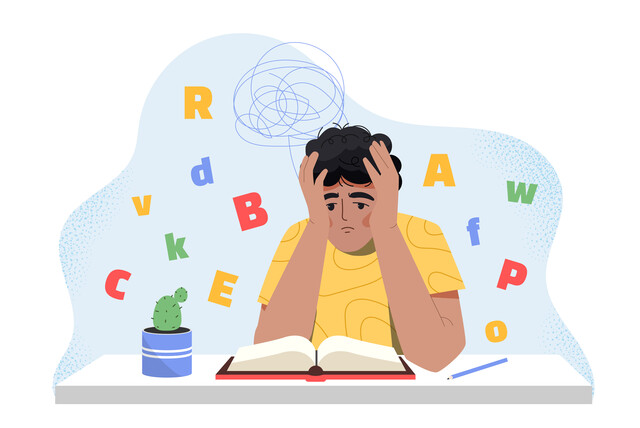

As mentioned earlier, learning disabilities are not to be equated with brain dysfunction, slow learners, or an ongoing or chronic handicap. A diagnosis of a learning disability does not in any way imply that a child or adult is of lower than average intelligence, experiencing either behavioral or emotional difficulties, or is at a disadvantage based on culture or demographics.

Again, the mere and rather dramatic increase in children identified with learning disabilities in recent years has caused numerous researchers to question the criteria, the definitions of learning disabilities, and the validity of various assessments and identification of learning disability processes. Indeed, many believe that the "learning disability" term is overly broad and that specific types of disabilities should be labeled or defined in a less ambiguous manner.

Biology, genetics, brain trauma, and brain developmental issues all come into play for many children requiring special education, as do levels of severity. In some school districts, interventions may be several years delayed depending on identification, diagnosis, and ability to accommodate to those needs.

A traditional special education class environment is often broken down into four different categories. For example, a special-education student may be placed in a special room with a small group of students with a greater teacher-to-student ratio. This may provide a more relaxed routine and structure within "regular" classroom environments.

A self-contained "special-ed" classroom removes a learning-disabled child from the general school population, overseen by a specially trained special-education teacher. These instructors may utilize different textbooks, offer a variety of academic levels, and a different curriculum than their same-aged peers learn in the "regular" classroom.

A third type is called a district placement, where a child is sent to a different school entirely, enrolled in a school that specializes in specific learning, as well as behavior based scenarios, while an inclusion class defines mainstream placement of a learning-disabled child with his peers in a mainstream classroom. In this environment, the instructor oversees the child's development. This instructor may adjust or adapt regular classroom activities, assignments and curriculum to better meet the child's specific needs. While this is typically the best scenario, as it promotes social, emotional, and behavioral development and growth, the student-to-teacher ratio, as well as the level of needs of the child, may not always be met in such an environment.

When a parent or teacher is considering a special class for a student, educators and parents need to ask themselves several questions. For example, why does a general education classroom, even with supplementary aids and services, not meet a student's specific needs? When considering including the learning-disabled child in a "mainstream" learning environment, one must always take into account the level of time the teacher may need to spend with the child, the potential for disruption, and the degree to which curriculum and classroom instruction will need to be adapted.

Before any student, regardless of age, is placed in any type of special-education class or service, educators and parents should be satisfied that special-education teacher support and accommodations for the student in mainstream classrooms have been considered and attempted, and that the child has had access to supplementary aids and services.

Creating Educational Development Plans

When it comes to interventions for the learning disabled, a number of methods have been utilized, and are currently under further development in school districts around the country. Due to the diverse types of learning disabilities and varying levels of severity, creating a "one-size-fits-all" development plan is impossible. Multiple aspects must be taken into consideration, such as the age of the child, his or her overall development, instructional scenarios, both in mainstream classrooms or special-education classrooms or groups, as well as combinations of each.

In addition, the term "different strokes for different folks" also applies to teachers and teacher approaches. For example, focus and guidance in phonological awareness instruction for children at the kindergarten level has shown positive effects and results in reading development of first-graders. This implies, that with proper teaching, guidance and instruction, knowledgeable teachers can help prevent reading failure in children diagnosed with learning disabilities -- not only in reading, but in language development activities.

As mentioned earlier, some children are not recognized with a reading disability, or any other type of learning disability until perhaps the third grade, when levels of homework, classroom involvement, and expectations rise beyond curriculum and demands for kindergarteners, first graders, and second graders.

However, based on a study, 65 dyslexic children with severe levels of disability were given 65 hours of one-on-one instruction, as well as focus on analytical, synthetic, and phonemic awareness. They improved reading scores from an approximately 77 to a 98.4 average in alphabetic reading skills.[2]

Such short-term educational development plans have shown positive results since those studies were completed in the early 1990s. In determining academic placement, older students today are assessed to determine what they do and don't know about math, reading, or writing skills.

In conjunction with Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment System testing (CASAS) and Tests for Adult Basic Education (TABE), assessment tests help determine proper classroom placement for older students -- high school, college and adult education -- as well as provide an ongoing review and documentation of aptitude level changes and progress. We mention that such tests listed above serve as the main, and most commonly used, tools in regard to academic placement challenges faced by teachers and school districts.

Long-term plans must always include a focus on "mainstreaming" a student into a regular classroom environment as often as possible. Most children and teens diagnosed with learning disabilities are able to maintain a presence in general education or "mainstream" classroom environments, with nominal disruption to either curriculum, additional time required by a teacher, or disruption to other students.

In many scenarios today, it is up to the parents to provide the extra time and support in helping their child either adapt to, or improve in, certain areas of education. Unfortunately, this is not always possible, due to numerous scenarios and factors.

Conclusion

Academic placement challenges and questions of whether accommodations are meeting classroom environments will continue when it comes to the learning disabled. As mentioned in this articlecreating an educational development plan that adequately meets the short- and long-term needs of the student is difficult.

Introduction

Learning disabilities and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, more commonly known as ADHD, are often confused, interchanged, or overlap in regard to symptoms, signs and student abilities. In this lesson, we're going to define the difference between a learning disability and ADHD, and how ADHD specifically affects learning in children and adults, as opposed to the challenges that face many people diagnosed with numerous types of learning disabilities.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is defined as someone with a short or poor attention span and impulsive behaviors. These impulsive behaviors may be termed inappropriate based on a child's age. Again, we must stress that many children are active and exuberant during various stages of development, and this exuberance, while often misdiagnosed as hyperactivity, is often perfectly normal.

It's estimated that roughly 5 percent to 10 percent of all school-aged children are diagnosed with attention deficit or hyperactivity disorder, and the prevalence of diagnosis occurs 10 times more often in boys than girls. In many cases, child experts believe that signs and symptoms of ADHD may be diagnosed before the age of four, and most often before the age of seven. Parents and teachers should be aware of the signs and symptoms of learning disabilities, as well as the most common signs and symptoms of ADHD to determine if their child may be dealing with some of these issues.

The severity of ADHD depends on the child, genetic factors, and abnormalities found in the neurotransmitters of the brain. Neurotransmitters are responsible for transmitting nerve impulses within the brain. Some children exhibit symptoms of ADHD in specific environments, such as scenarios where the structure of instruction interferes with the ability of the child to deal with such issues � a classroom, the place the child typically completes homework in the home environment, and so forth.

Growing numbers of children are diagnosed with ADHD, although doctors today as well as parents are concerned that many of them have been misdiagnosed. We all know that two-year-olds are generally active, and their enthusiasm for learning about their environment is seemingly endless. High levels of activity and noise are very common in children up to the age of about four. It's not often easy to determine whether a child's activity levels are abnormally high. In many cases, such frustration depends on the tolerance level of the parent, caregiver or teacher.

Symptoms of ADHD

Symptoms of ADHD are not always easy to identify, especially when based solely on age. Children's personalities, activity levels, and behaviors may not be the same every day, nor are teachers likely to experience the same activity from the same child on a daily basis. Again, behavior and symptoms, as well as signs, are based on scenario, situation, stress levels, and environment.

The following signs of ADHD are not meant to be all-inclusive, and not every sign or symptom has to be present for a professional to make a diagnosis of ADHD. For example, in order for a sign or symptom to be seriously considered, it should occur in more than one environment. For example, a sign or symptom at school alone is not enough to make a diagnosis, but signs and symptoms in two very different environments such as school and home, or school and church, may help guide parents and teachers toward a diagnosis.

However, in order to be diagnosed properly, such signs and symptoms, are classified according to whether those symptoms interrupt or interfere with academic or social function in a variety of environments.

The most common signs of hyperactivity include:

- Excessive fidgeting of the hands or feet, and may also include "squirming"

- A child who often leaves his or her seat in the classroom, at the dinner table, or in another structured environment, despite numerous attempts to remind him or her to remain seated

- A child who is especially rambunctious, or climbs or runs around, even when he or she has been told not to do so (Again, some children are just especially active and this alone does not indicate that a child is hyperactive.)

- A child who has difficulty quietly engaging or playing with others or by him or herself -- key word here is "quietly"

- A child who seems to run endlessly on "batteries," or who is so active that he or she never seems to run out of energy

- Excessive talking (Again, some children are especially exuberant and excited about their environment, and want to share their thoughts, impressions, and ideas more than others.)

The most common signs of inattention (in children and adults) include:

- A person who can't seem to pay focused attention to details

- A person who has a very short attention span, or difficulty focusing in either work or play scenarios

- A person who seems continually distracted, or whose thoughts continually wander elsewhere when being directly spoken to

- A person who finds it difficult or is unwilling to follow instructions, or finds it extremely difficult to finish a task

- A person who has difficulty organizing a task or an activity (We all have lapses once in a while, but this sign, to be classified as a sign of ADHD, is chronic.)

- A person, child or adult, who seems to go out of their way to avoid, or expresses dislike in any task or activity that requires a consistent or sustained mental effort or focus

- A child or adult who constantly loses things (Again, many of us experience this, and by itself, this is not a sign of ADHD.)

- A person who is very easily distracted by environmental stimulus, or who finds him or herself easily distracted in a work, home, or play environment

- A person who is very often forgetful (Again, this sign alone is no indication of ADHD.)

Individuals diagnosed with ADHD are also often impulsive. In regard to impulsivity, this defines a child or adult who may be impatient for a question to be completed before he or she feels compelled to blurt out an answer. Such individuals also display an inability to wait his or her turn, and ten interrupts someone else.

As you can see -- ADHD and learning disabilities are not the same, though approximately 20 percent of children diagnosed with ADHD dohave learning disabilities of some sort. Roughly 80 percent of individuals diagnosed with ADHD have difficulty with academics, but this is based on their inability to focus or concentrate, rather than on brain-oriented learning disabilities such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, or dystonia.

Several signs of ADHD and learning disabilities overlap. For example, a child diagnosed with ADHD may have very messy writing, but often, their writing or calculations are the result of careless mistakes, as well as the result of rushing to come to a conclusion or an answer, rather than an inability to do so. One of the most common signs of a child with ADHD is one whose mind seems to be somewhere else when someone else is talking to them.

As with learning disabilities, a child diagnosed with ADHD may have very serious issues with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. Some show a very visible display against authority by the time they reach their teenage years, and nearly 60 percent of younger children express their displeasure in very vocal temper tantrums.

To reiterate, ADHD is defined as a disorder in a person with a very short or poor attention span, often accompanied by hyperactivity and impulsiveness. A learning disability or disorder defines an inability to receive, retain, or use specific information or skills, often resulting from a deficiency in memory, reasoning, or attention.

As with learning disabilities, children with ADHD require a structured school environment and intervention plans, as well as educational development plans that will stand a child with ADHD in good stead. In many cases, children diagnosed with ADHD are given drugs like methylphenidate, a psychostimulant. Some such medications may promote side effects such as sleep disturbances, including insomnia, headaches, stomach aches, and depression. In children, very few side effects are noted, except for a decreased appetite.

Additional drugs are often prescribed in the treatment of ADHD, including antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications, amphetamine-based drugs and Clonidine. In most cases, a child diagnosed with ADHD will not outgrow the condition, although he or she may able to somewhat calm their impulsive and hyperactivity urges with age. Most learn to adapt to their short attention span, while some do not.

Conclusion