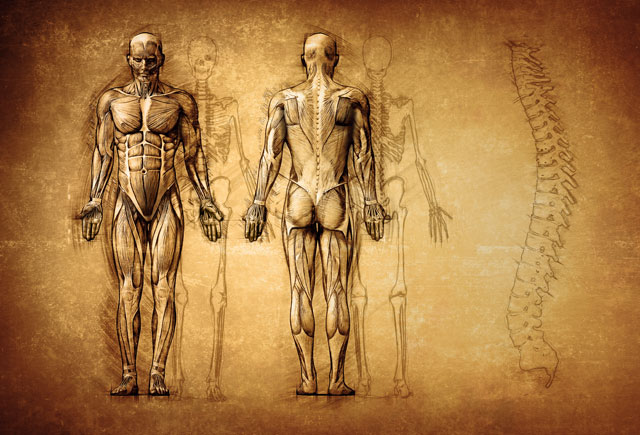

Physiologically speaking, the human digestive system processes food in order to supply the body with the nutrients that it needs to function properly. Anatomically speaking, the digestive system is made up of the digestive tract and other organs that help the body break down and absorb food. Therefore, the two main functions of the digestive system are to digest the food we eat into small molecules and absorb these molecules into the bloodstream through the circulatory system to provide fuel for the body.

The digestive tract is basically a long tube, about 30 feet in total length, which starts at the mouth and ends at the anus, traveling through various organs that play a part in digestion.

The digestive system is important because food, whether liquid or solid, has to be broken down into molecules of nutrients so that they can be absorbed into the blood and transported to the body's cells.

The gastrointestinal tract, also known as the alimentary canal, includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus.

Food moves from one organ to the next through a wave like involuntary muscle movement called peristalsis. So while the act of swallowing is voluntary, once the food is in the esophagus, the nervous system takes over using peristalsis.

These organs include the teeth, the tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and the pancreas.

The Digestive Process

The chewed clump of food we swallowed, called a bolus, makes its way down the esophagus and into the stomach. The stomach has three primary functions:

- Store food and liquid.

- Mix food, liquid, and gastric juices together.

- Empty the stomach contents slowly into the small intestine.

The stomach, which is filled with gastric acid, churns the boluses with the gastric acid to break them down into smaller bits. The food-gastric acid mixture is called chyme.

The chyme eventually leaves the stomach and travels through the small intestine, which has three areas: duodenum (beginning), jejunum (middle), and ileum (end). The average adult small intestine is about 20-25 feet long.

While in the small intestine, bile, pancreatic enzymes, and other digestive enzymes secreted by the inner wall of the small intestine further break down the food into molecules that cells can use.

Digestive Organs

The liver and the pancreas produce digestive juices which are passed to the small intestine through small tubes called ducts. The pancreatic juices help the body digest fats and protein. Bile from the liver helps with fat absorption. The bile produced by the liver is stored in the gallbladder until needed in the intestine.

The Liver's Role

The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, weighing on average around three and a half pounds. It's also the largest gland, as it secretes bile.

The bile produced by the liver emulsifies fat into smaller droplets that are easier for the digestive system to process. When food containing fat reaches the duodenum, the body secretes a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK), which prompts the release of bile into digestive tract.

The liver also works as a filter to remove products from the bloodstream which we don't need or that could be harmful, such as alcohol from liquor.

When the blood reaches the intestines, a set of capillaries takes the blood to the liver, which filters out any products that the body does not need and deposits them back into the digestive tract to be excreted either in urine or in feces.

Absorption

The mucosa of the small intestine is covered with tiny fingerlike projections called villi. The villi, in turn, are covered with microscopic projections called microvilli. These structures create a vast surface area through which nutrients can be absorbed. Specialized cells allow absorbed materials to cross the mucosa and into the blood, where they are carried off in the bloodstream to other parts of the body for storage or further chemical change.

The Break Down of Food

Different types of food each have different digestive processes.

Proteins must be digested by enzymes before they can be used to build and repair body tissues. An enzyme in gastric acid starts the digestion of ingested protein, which is continued in the small intestine where enzymes from the pancreatic juice and the lining of the intestine complete the break down of protein molecules into amino acids.

The digestion of carbohydrates begins when enzymes in the saliva and pancreatic juice break it down into simpler molecules called maltose. An enzyme in the lining of the small intestine then splits the maltose into glucose molecules that can be absorbed into the blood. Glucose is carried through the bloodstream to the liver, where it is stored or used to provide energy.

Sugars, on the other hand, are digested in one step. An enzyme in the lining of the small intestine digests sucrose, the same sugar we use to sweeten our drinks and cook with, into glucose and fructose, which are absorbed through the intestines into the blood. Another type of sugar, lactose, which is found in milk, is also broken down by another enzyme in the intestinal lining called lactase. A deficiency in lactase is what makes people lactose intolerant.

Fiber is indigestible and cannot be broken down by enzymes. Soluble fiber dissolves easily in water and takes on a soft, gel-like texture in the intestines. Insoluble fiber passes essentially unchanged through the intestines.

Fats, or lipids, are organic compounds composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. They do not dissolve in water and are not easily broken down by fat digesting enzymes so fats tend to take longer to digest than carbohydrates or proteins.

Fat digestion doesn't really begin until it reaches the duodenum where it encounters the pancreatic enzyme lipase, which breaks up lipid molecules into fatty acid and glycerol molecules. Bile emulsifies the fats into smaller droplets which are suspended in the watery chyme, making it easier for the lipase to then break down the fats.

|

Organ/Enzyme |

Substrate |

Products of Enzyme Activity |

|

Mouth |

||

|

salivary amylase |

starches |

maltose, oligosaccharides |

|

Stomach |

||

|

pepsin |

proteins |

peptides |

|

Pancreas |

||

|

pancreatic amylase |

starches |

maltose, oligosaccharides |

|

trypsin |

proteins |

peptides |

|

chymotrypsin |

proteins |

peptides |

|

carboxypeptidase |

proteins |

peptides, amino acids |

|

pancreatic lipase |

fats |

fatty acids, monoglycerides |

|

nucleases |

RNA & DNA |

nucleotides |

|

Small intestine |

||

|

dextrinase |

oligosaccharides |

glucose |

|

maltase |

maltose |

glucose |

|

sucrase |

sucrose |

glucose & fructose |

|

lactase |

lactose |

glucose & galactose |

|

aminopeptidase |

peptides |

peptides, amino acids |

|

dipeptidase |

dipeptides |

amino acids |

|

nucleosidases |

nucleotides |

nitrogen bases, ribose, deoxyribose & phosphates |

|

phosphatases |

nucleotides |

nitrogen bases, ribose, deoxyribose & phosphates |

The Colon

The ileum is connected to the large intestine by a pouch called the cecum. The appendix, which has no known modern function, is attached to the cecum. Food travels from the cecum upward in the ascending colon, across the transverse colon, and then down the descending colon, where it then goes through the sigmoid colon, which connects the descending colon with the rectum. As the food travels through the large intestine water is removed along with various chemicals until what is left is solid waste, called feces, that is unusable by the body. The feces is stored in the rectum until excreted through the anus.

The Endocrine System's Role in Digestion

Cells in the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine produce hormones that control the functions of the digestive system. These hormones stimulate digestive juices and cause organ movement.

There are three primary hormones that control digestion:

- Gastrin causes the stomach to produce an acid for dissolving and digesting some foods. Gastrin is also necessary for normal cell growth in the lining of the stomach, small intestine, and colon.

- Secretin prompts the pancreas to emit a digestive juice rich in bicarbonate, which helps neutralize the acidic stomach contents as they enter the small intestine. Secretin also stimulates the stomach to produce pepsin, an enzyme that digests protein and stimulates the liver to produce bile.

- CCK (Cholecystokinin) prompts the pancreas to produce pancreatic juice enzymes and directs the gallbladder to empty. It also promotes normal cell growth of the pancreas.

Other hormones in the digestive system regulate appetite. Ghrelin, is produced in the stomach and upper intestine when there is no food present; this stimulates the appetite.

Peptide YY is produced in the digestive tract in response to food and inhibits appetite.

The Role of the Nervous System in Digestion

Two types of nerves help control digestion.

The extrinsic nerves arrive at the digestive organs from the brain or the spinal cord and release acetylcholine and adrenaline.

Acetylcholine prompts the muscles of the digestive organs to squeeze harder to propel food through the digestive tract. It also directs the stomach and pancreas to produce more digestive juices.

Adrenaline does the opposite; it relaxes stomach and intestine muscles and decreases the flow of blood to these organs, which slows or stops digestion.

The intrinsic nerves are embedded in the walls of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon. These nerves are triggered when the walls of the hollow organs are stretched by food, prompting them to release substances that either speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of juices by the digestive organs.

Conclusion