And, within the lending industry, the numerical calculations with which a loan officer will be faced include: deciphering a total loan amount, deciphering amortization periods, tabulating interest rates and payment frequencies.

There is also the matter of point fees, remunerations earned by the loan officer. Such additional charges are then added into the overall figure presented to the borrower as part of the total loan package.

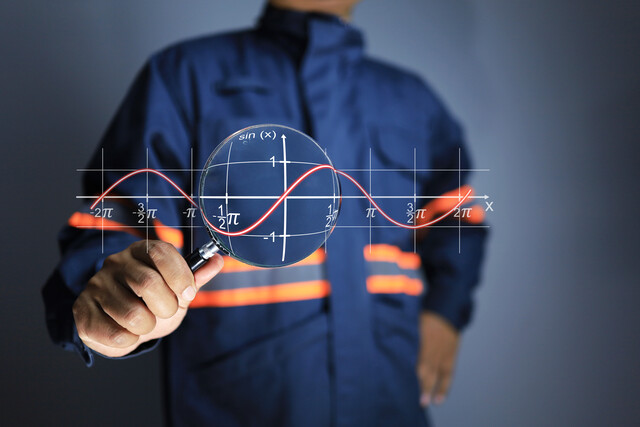

When attempting to precisely calculate the payment terms of the loan, such concepts as present value, future value, and annuity case scenarios come into play. Combined, they represent the timeline of an investment and the accompanying stream of payments. While discerning figures and amounts, what becomes clear is how specific values change over time.

Generally speaking, within a lending scenario, there is the simultaneous occurrence of the following two factors:

-

The original sum (the principal) grows in value as the interest accumulates over time.

-

Ideally, payments are being made on a regular basis. However, as part of the lending process, the payments are notated as negative for, initially, they are used to reduce the principal sum.

In the financial lending formula, there are the following five core parameters:

-

"n" is used to represent the total number of payments. While they usually tend to be monthly, they could be of other time intervals, as well.

-

The interest (p) in percent is used to represent paid per payment. For example, should the borrower, make regular monthly payments at an annual interest rate of 12% then the monthly interest payment, p would equal 1%.

-

The Principal Value, (PV) represents the amount of money one has borrowed.

-

The borrower's regular payment amount (pmt) is positive when a loan is paid off, and negative when money remains due.

-

The Future Value, (FV), of the investment is zero for those who completely pay off a loan, positive for those who save a certain amount of money and negative for those whose loan is structured as a balloon (large, inflated) payment at the end of the overall payment schedule.

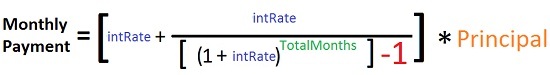

To determine the amount a borrower will need to pay on a monthly basis, loan officers tend to employ the following classic equation:

Based upon the aforementioned equation:

-

Payment is the monthly payment (this is what we are calculating).

-

intRate is the interest rate. Note: A 12% interest rate in APR terms is expressed by the Interest Rate divided by 1200 for a decimal number.

-

Principal is the amount of money being loaned.

-

TotalMonths is the number of payments for the life of a loan. For a 30-year loan it would be 360 monthly payments.

In the classic equation, it is assumed that the payment will be made monthly.

By deferring to the following formula program, loan officers can accurately calculate a borrower's monthly payment based upon a pre-specified principal, interest rate, and payment schedule.

Principal: _______.____________ (amount of money being loaned)

Interest rate: _______.________ (12% = 12/1200 = 0.01)

Total Number of months: _______. (15 years of monthly payments = 180)

(30 years of monthly payments = 360)

Interest Charges

This figure is a tell-tale sign as to whether a client will be able to consistently meet their regularly scheduled payments.

And while, at times, the calculation of interest rates can prove to be a complex task, the pared down method for deriving at such a figure can be simply defined as: the dollar amount of interest charged divided by the amount of money borrowed.

- Add-on method

- Discount method

- Remaining balance method

The interest charge is added to the principal to determine the total amount to be repaid. This amount is then divided by the number of repayment periods to determine each payment.

As such, the total interest charge is: I = A x ic x N, where I = total interest charge over the life span of the loan; A = amount of loan; ic= contractual interest rate per time period; and N = number of periods covered by the loan.

The periodic payment is: Bn = (A + I) / N, where B = total payment and n = repayment periods covered under the loan.

For an example of add-on interest, assume a $10,000 loan is to be repaid in two annual installments. The annual contractual interest rate is 6 percent. Then, the total interest charge is: I = $10,000 x .06 x 2 = $1,200 and the annual payments will be: B = ($10,000 + $1,200) / 2 = $5,600.

Very similar to the Add-on Method, the Discount Method calculates total interest in nearly the same way with the one exception that the interest is subtracted from the loan amount and the borrower receives the balance.

As such, the total interest charge is: I = A x ic x N.

I = $10,000 x .06 x 2 = $1,200.

The borrower would receive $8,800: L = $10,000 - $1,200 = $8,800 and would repay two installments of $5,000 each: Bn = $10,000 / 2 = $5,000.

The major difference between the Remaining Balance Method and the previous two, Add-on and Discount, is that beyond the complexity of the mathematical calculations, interest is not charged on principal that has already been repaid.

And while the loan officer can make suggestions, the decided loan structure payment ultimately is the decision of the borrower.

The major structures from which a borrower can opt include:

Lump sum repayment. The borrower agrees to pay principal and interest in one lump sum at the end of one year. Hence, if $5,000 is borrowed for a one-year period at a 6% interest rate, then at the end of the year, the borrower would need to repay $5300, the principal + interest.

Periodic interest and lump sum repayment of principal. Under such a structured arrangement, the borrower consents to solely paying off the interest during the first two years and, at the end of the third year, paying off the interest and the principal. On account of the big payment at the end of the term, this type of loan is often referred to as a balloon loan. As an example, a borrower of $10,000 at 10% would pay $1,000 in interest at the end of the first and second years, and then $10,000 in principal and $1,000 in interest at the end of the third year.

Periodic payments of principal and interest. In this payment plan, the borrower agrees to repay portions of the principal each year of the loan (a typical term is a four-year loan period) along with interest at the end of each year.

As such, according to this type of structure ($10,000 at 10%), a borrower's payments would adhere to the following schedule:

End of Year One: $2,500 principal + $1,000 interest

End of Year Two: $2,500 principal + $750 interest

End of Year Three: $2,500 principal + 500 interest

End of Year Four: $2,500 principal + $250 interest

Amortized payments. These are defined as payments equally spread out over time, within this type of plan, the borrower signs on to make identical monthly payments so that over the course of a five-year period, the principal and interest will be fully repaid.

With amortized payments, it is common to refer to an amortization table (either in a book or online) to determine the monthly amount that must be paid over the course of five years in order to fully pay off a $10,000 loan along with the current interest rate.

Amortized payments with a balloon. In this type of loan structure, though the borrower plans on making equal monthly payments based upon a five-year amortization schedule, they agree to pay off the remaining principal at the end of the third year.